Why do Gibson headstocks break?

Most Gibson guitars have a one-piece neck that really, really wants to be in two pieces. 😉

That’s a bit flippant, but most instrument repairers will tell you that Gibson headstock breaks form the bulk of their neck repairs. Gibson guitars are neck repairs waiting to happen and, to continue the bad news, there’s not a huge amount you can do about it.

Except maybe understand it and some of its context.

Background: Angled Headstocks

In order to keep your strings properly seated in the nut slots, they need to ‘break’ over the nut at an angle. With a straight headstock, like the Fender-style, string-trees are one method used to increase the nut break angle.

Other instruments choose to angle the entire headstock back to accomplish this. It’s certainly effective but, depending on how the neck and headstock is constructed, it can introduce problems.

Gibson One-Piece Neck Construction

Many Gibson guitar necks are cut entirely from a single piece of timber. This has been touted as a selling point — the rational being that a single piece of timber will resonate as one and lead to better tone.

The problem, however, is that this single piece of timber introduces a very specific and nasty weakness.

With the grain running along the neck length, you have a very strong piece of wood. It'll resist bending and breaking nicely.

However, where the headstock angles, this strength becomes a weakness.

When you cut an entire neck out of a single piece of wood, the angled headstock adds an incredibly effective ‘fault line’. As luck would have it, that fault line occurs at what is already the thinnest and weakest part of the neck — where the headstock ‘leaves’ the neck. The 'shorter' section of grain here is much more susceptible to splitting or breaking apart.

Then, after making a neck with a natural fault line at its weakest point, Gibson then cuts a hunk of wood from the front of that weak area to accommodate a truss rod wrench. The truss rod access further weakens this area.

What can builders do to prevent broken necks?

I’m going to paraphrase something I read years ago (and I can’t remember an attribution for it):

“Porsche designers decided to put the engine of the 911 over the rear axle and have spent the last fifty years trying to make a car defy physics because of that decision.”

I like to think of angled headstocks in a similar way.

You could think of an angled headstock as almost a design flaw. But it’s got something pretty great about it so, now we need to find a way to defy physics so it doesn’t keep snapping off.

No one idea is the answer but there are ways to make the snapping, at least a little, less likely.

The Volute

The easiest way to help things is to add some wood at that weakest point. A volute is just a protrusion on the rear of the neck-headstock join. This adds a little strength and, while it’s not a guarantee, can certainly help.

At different points in its history, Gibson has added volutes to their guitars. And then taken them away again. As of writing, though, they are beginning to introduce volutes on some models so, it’s possible we’ll see more in the future. Not a bad thing.

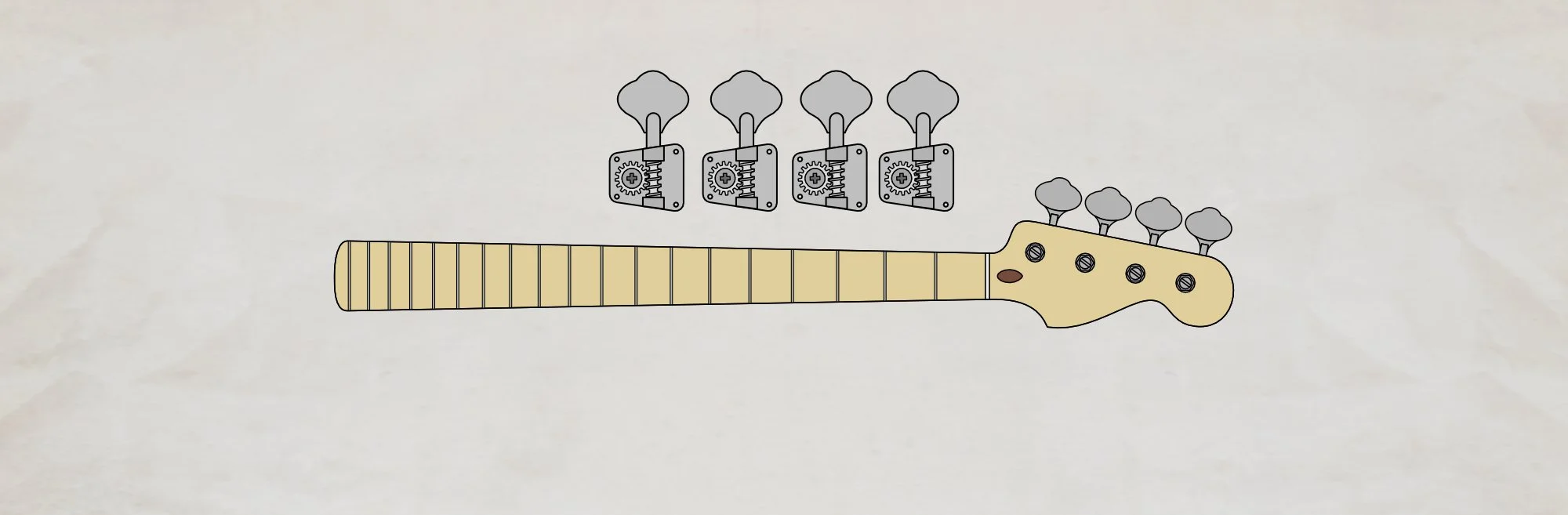

Two-Piece Neck

A more certain solution is to forget about making a one-piece neck (which is actually incredibly wasteful anyway). Jointing and glueing a headstock on to the end of a neck makes for a considerably stronger neck.

By cutting a piece from the end of a neck blank, flipping it and glueing it back on at an angle (as shown above) we can actually make that grain direction thing work for us rather than against us. Jointing a headstock on can be accomplished in a number of different ways but the theory is pretty much the same as illustrated. A good glue joint is strong. No grain fault-lines exist and the end result is a strong neck.

Purists claim it won’t ‘resonate’ in the same way but, as with so many claims, I’d really love to perform some properly blinded testing on this.

Straight neck

Not sure if it’s fair to mention a straight neck as a solution but Fender-style necks are certainly stronger than their angled counterparts. Again, the grain all goes in the same direction so it’s less likely to crack. Not impossible, of course but, all things being equal, you’ll have fewer Fender headstock cracking than Gibson.

In Gibson’s Defence

I know I’ve done a lot of Gibson-bashing in this one. That’s (partially) unfair. Gibson are not the only guitar manufacturer to make guitar necks like this. They are the biggest and best known though.

And, as noted, the company seems to be revisiting the volute, at least on some of their models.

Lastly, in Gibson’s defence, they have a really, really hard time changing anything. If they announced, proudly, that they were going to scarf-joint all their headstocks, guitar nerds the world over would take to the forums and decry it. “But our tone! Gibson-fail! Headstock-gate!” There is a very invested, and vocal, ‘lobby’ of conservative Gibson fans. Many, many people do not like it when the Big G makes a change.

So, for the most part, many Gibson one-piece guitar necks will continue to fulfil their destinies by becoming two piece necks.

What can players do to prevent broken necks?

Don’t drop your guitar.

Yeah, I know. Not hugely helpful, is it?

But, other than being careful, there’s not a huge amount I can suggest. Just don’t drop it.

And don’t assume that being in a case will help. I’ve worked on plenty of Gibsons that suffered headstock breaks after falling in their cases.

Sucks, I know.

Be careful.

And on that depressing note, I’ll take my leave. Sorry.

This article written by Gerry Hayes and first published at hazeguitars.com